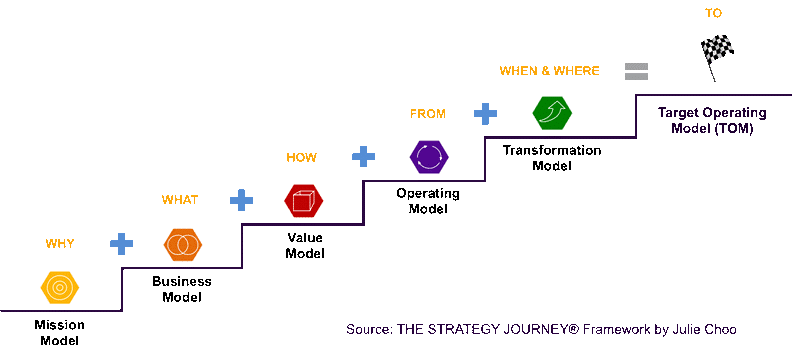

In my last article, I talked about some of the key aspects you must consider when defining a target operating model. In this follow up piece I have delved a little deeper and will look at how TOM initiatives can vary across different types of businesses; from large corporates to start-ups and government organisations.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF TARGET OPERATING MODELS (TOMS)

The future state TOM varies depending on what industry an enterprise is in, the level of innovation, and what needs to be achieved. This would represented by the outcomes that are sought through the strategies of that particular enterprise.

TOMS IN LARGER ORGANISATIONS

In many of the larger incumbent organisations that I have worked for and with, change and innovation, if it exists, is unfortunately rather slow. Most larger organisations give themselves 3-5 years to change their overall strategy journey. This is certainly realistic if they are looking at a specific business line and re-evaluating their strategic goals and objectives, as well as their business model.

In some projects, TOM changes are expected in 1-2 years, but this is usually the result of a short-term tactical change, rather than a proper TOM initiative, as the goal is usually to execute cost cutting in order to ensure the balance sheet looks good.

When the starting point or desired outcome is just cost cutting, the TOM project naturally becomes a vehicle for delivering organisational changes that are responsible for making people redundant, or relocating them to cheaper off-shore locations. It might implement a new strategy to work and service customers remotely, or even move customers to a self-serve model.

If these changes are implemented without first considering if a business model change is required, or what the implications or impact to the business model and the value model are, then that organisation is likely to only achieve that immediate short-term balance sheet adjustment. There will be a lack of any other potential benefits, which would form part of a more holistic strategy that will deliver longer-term benefits. Worse still, the short-term gains may also lead to longer-term problems and pain down the track.

TOMs IN GOVERNMENT ORGANISATIONS

In government organisations that are looking at societal changes, the TOM can be a 25 year plan. This is the case with Singapore, who have a Vision that they want to achieve for 2050. In the UK, it is uncertain at this stage what the TOM looks like for Brexit, and exactly how long that will take to achieve. I suspect it could be a whole decade, so it will be interesting to see when a plan is announced and the projected outlook of that plan. Will it be for 2020, 2025 or even further into the future?

A STARTUP TOM

In start-ups, where the fight is for survival, some would argue that it is unrealistic to look beyond just 1 year to 18 months. Things are likely to change so quickly, and it may feel like there

While we all view Google as a tech giant today, that certainly wasn’t the case in its early years from 1998 to 2003. Back then, Yahoo was the big market player and Google was an emerging start-up that bootstrapped in order to fund investments in its technology and infrastructure for the longer term. This allowed it to outpace its rivals.

At this time Yahoo was busy looking at customer acquisition strategies and marketing, to build a large market share. It decided to outsource infrastructure components to strategic partners as well as simply using more people to build its online search catalogue.

Google took a longer-term strategy and focused its efforts on getting its operating model elements right. It built capabilities so that it could scale exponentially when the time was right, to showcase its new, more disruptive, product offerings to the market. In the end, Yahoo couldn’t keep up with the cost of maintaining its business. It invested in the wrong things in order to compete, even overlooking its security, while Google swiftly found a way to entice Yahoo’s customer base over to its new, better, faster and more robust products.

TOMS IN HIGH-PERFORMANCE SPORTS ORGANISATIONS

F1 is an incubator for innovation, because change is so rapid. Changing regulations require architects, like Adrian Newey from Red Bull Racing, and engineers to design a new car and engine every year. Each track is different, requiring the car and the driver to have a different set up in order to have the fastest car possible for each race. Weather conditions can change the balance of a car on any given day, or even during a race. This affects how the drivers must adapt to race properly. In F1, it is safe to say that a TOM, if it exists, is no more than a year. It is under constant scrutiny and change, so it needs to be highly agile.

In most sporting organisations, like football teams, a TOM can be driven by their yearly season, or a 4-year Olympic or World Cup cycle. Again, conditions and circumstances change. With athletes gaining injuries that can affect team performance, sporting organisations need flexible teams and a highly agile operating model to fight for their successes and victories. Of course, we know the Germans decided to develop a 10-year TOM spanning multiple World Cup cycles. It took that long to build and develop a team from a youth squad into the 2014 World Cup Champions.

TARGET OPERATING MODELS (TOMS) THAT DELIVER

A TOM will deliver whatever you ask it to do. So, the most important step to developing a good TOM is to ensure it is being formulated for the right outcomes. These outcomes need to clearly state what the goals are and how, when and where they will be achieved. If the mission, goals and objectives are compromised to begin with, and not properly aligned to the strategy of your organisation, then naturally, the output of the TOM will reap the benefits as well as consequences of that compromise. In Big Data the saying goes: rubbish in, rubbish out.

When the TOM is designed to deliver in phases, and is aligned across all THE STRATEGY JOURNEY stages, with the 5 strategy journey models in sync to deliver the right outcomes, with a plan to execute those phases in the right place at the right time, while having the agility to cater to unforeseen changes, then an enterprise is in the position to successfully navigate its journey to deliver the outcomes in the TOM and the benefits sought.